Today it is widely accepted that inclusion maximizes the potential of the vast majority of students, ensures their rights, and is the preferred educational approach for the 21st century. Unfortunately, the philosophy has not always been widely held. Our thinking and acceptance has evolved rapidly over the last century, and continues to evolve, in response to federal and state law, along with our changing social and political beliefs.

Think back. When compulsory public education began near the turn of the century, no public school programs existed for students with disabilities. Schools were expected to be efficient assembly lines, with each class of students moving from grade to grade and, eventually, graduating from high school as productive citizens prepared to enter the workforce. Special classes, at first, did not exist. Later, they were developed as a place for students who could not meet the standards and keep pace with fellow classmates.

By the 1950s, special education public programs were available in many school districts, but some undesirable outcomes were becoming apparent. Many authorities in the field agreed that segregated special classes were not an appropriate educational setting for most students with special needs, for it was clear that educating students with special needs in isolated settings minimized, rather than maximized, their potential.

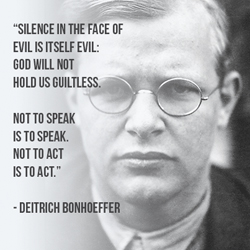

Simultaneously, the Civil Rights Movement was in its great surge, and the fights for equal rights and non-discriminatory laws were being culminated in the U.S. Supreme Court with the historic Brown Decision. In 1954, the case of Brown vs. the Board of Education established the principle that school segregation denies students equal educational opportunity. Although the decision referred to racial segregation, it began to influence our thinking about people with disabilities. The thinking went something like this: if separate is not equal, what about our children with special needs being denied the right to a free and public education, or being placed in separate, segregated, classrooms?

One of the outcomes of the Civil Rights Movement is the enactment of legislation designed to prevent discrimination against individuals with special needs, whether they are children in schools or adults in the workforce.

In the early 1970s, landmark civil rights legislation opened the door for all children with special needs to receive a free and public education, and ensured equal opportunity for students to participate in the full range of school activities.

The 1997 reauthorization of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) specifically supports inclusive thinking and practices. IDEAcalls for involving students with special needs in general education curricula, assessment practices, and classrooms. Recognizing that traditional strategies result in a lack of learning outcomes for students with special needs, relative to outcomes of comparable peers without special education labels, IDEA encourages general and special education teachers to work together for the benefit of each and every student. The Committee Report that accompanied the new law to Congress explains the legislators’ intent: inclusion is a philosophy of acceptance and flexibility.

On January 8, 2002, the No Child Left Behind Act was signed into law. The legislation bolsters the philosophy that the majority of students with special needs be moved out of segregated classrooms, and given the appropriate strategies, accommodations, and teaching styles to match their unique learning styles. The No Child Left Behind Act builds on four principles for education reform: accountability for results, doing what works based on scientific research, expanded parent options, and expanded local control and flexibility.

At a fundamental level, inclusion is really about fairness. Responding to each student based on need is the meaning of fairness. In the past schools could hide achievement results by excluding students with special needs. This is no longer possible. No Child Left Behind has changed the landscape of education by shifting the focus from compliance to outcome; it requires us to measure the progress of all our students so thatevery child can realize the great promise of America.